For many, including those with family connections to Scotland, a highlight of any tour that includes Inverness and the Scottish Highlands is a visit to Culloden Battlefield. The barren heathland of Drumossie Moor, just a few miles from the centre of bustling Inverness, is an evocative place. Many are deeply moved by the stories of bloody warfare, great personal heroism, and brutal post-battle retribution.

The battle that unfolded in just under an hour, on 16th April 1746, was a pivotal moment in British history. It is an event that continues to attract historic research, as well as intense academic debate but over the centuries many myths and legends have established themselves in popular views about the battle.

This was a battle between England and Scotland.

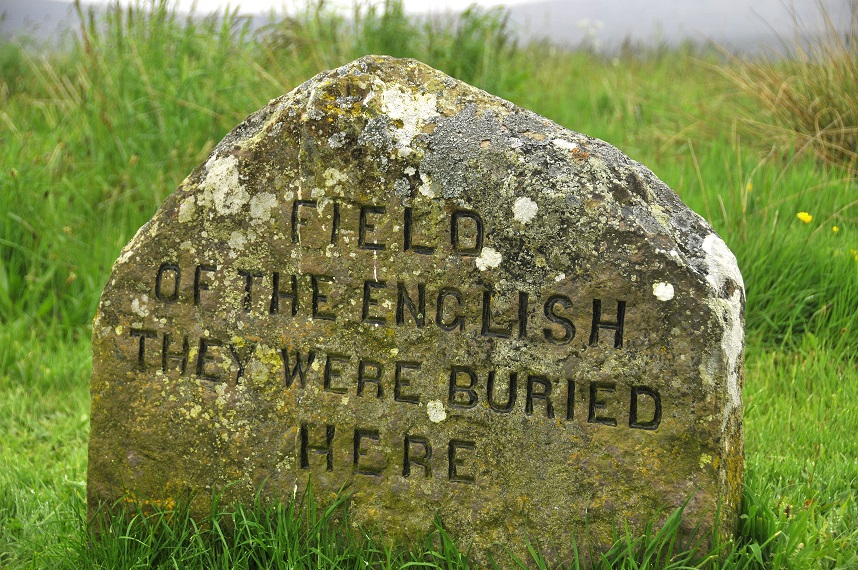

Even today you will hear this view expressed on the battlefield, even by some tour guides. It is a viewpoint helped by the enigmatic stone that says “Field of the English” suggesting that is where government casualties are buried. However, like many other aspects of the battle it is more complicated than that.

There is no doubt that the Act of Union in 1707 that created Britain, was deeply unpopular amongst many in Scotland. As a result, there was a swell in Scottish patriotic fervour, which was a powerful recruiting sergeant for the Jacobite cause. Many backing the Stuart cause saw it as a way of regaining Scottish independence. However, Jacobites came from across the British Isles, and had a very international flavour. They were united in the cause to return the Stuart royal family to the thrones of England, Scotland, and Ireland.

This was a religious conflict between Catholics and Protestants

As the Stuarts were staunch and devout Catholics it is often assumed the battle was between Catholic and Protestants. It was the support for the Catholic faith that contributed to James II and VII’s downfall, and his eventual exile in continental Europe. To be followed by the placement of William and Mary as defenders of the Protestant faith on the throne.

Yet again, it is not as simple as Catholic versus Protestant. Statistically those fighting the Jacobite cause were more likely to be Protestants – a mixture, of high Anglican, Episcopalian, or dissenters. There was a hope particularly, amongst Episcopalians that the restoration of a Stuart monarch would lead to more religious tolerance and the Presbyterian grip that was felt most strongly in Scotland would weaken. In fact, many leading Catholics, such as the Duke of Norfolk never wavered in their support for George II in 1745 as the Jacobites advanced towards London

Bonnie Prince Charlie chose the wrong place for the battle

It is often stated that the ground at Culloden was a decisive factor in the Jacobite defeat and that this was result of poor strategic decisions made by Charles Edward. The oft quoted plea from Lord George Murray, a key ally of the prince, of “not here, not today, sir!” is cited as evidence that the prince had got it wrong.

Lord Murray had certainly advocated another site to line up the opposing troops, which the prince decided to ignore. Another site had also been scouted but quickly discounted. There was little real choice as the moorland was close to the Jacobite headquarters at neighbouring Culloden House. And more importantly it was a defensive line to protect the road to Inverness, which the Jacobites had to hold at all costs.

This was a battle between a ragbag of Highlanders and a disciplined modern army

Or to put it slightly differently is to say that Culloden was a victory of muskets over swords. Although the Jacobites were heavily outnumbered by the advancing Hanoverian army there has been a long assumption that they were also outgunned. That it was artillery bombardment, followed by highly disciplined and drilled musket infantry that led to victory. And a Jacobite over-reliance on the famed, and feared, Highland Charge with claymores at the ready, that failed on the day. Both Gaelic poets and government propaganda from the time can be blamed for this myth.

The Jacobite army was not a primitive and barbaric army of clansmen. Recent historical research suggests that there were more guns, than swords deployed by the Jacobites at Culloden. And they were bolstered by cannons, many captured during previous battle victories. It was the swords of the advancing British cavalry cutting down Jacobite musketeers that proved the Jacobites downfall.

Prince Charles Edward Stewart was a coward and beat a hasty retreat

This is possibly as much to do with state propaganda in their portrayal of the battle following their victory. The government wished to paint the Jacobites in the worst possible light. Not only were they backward Highlanders but they were no longer the brave warriors of legend. After all they were led by a cowardly pretend prince. Lord Elcho’s frequently quoted jibe on the battlefield “There you go for a damn cowardly Italian” although probably a later embellishment compounds the myth.

Accounts suggest that far from turning like a coward, Charles was determined to carry on and throw himself into the fray, even though the battle was lost. It was his own commanders who lead him from the field to avoid complete destruction. From that moment onwards he was a hunted man with a £30,000 reward on offer for his capture. Amazingly, he was never betrayed as he criss-crossed the Highlands in the months that followed before his final escape back to France.

The Clan Graves mark the exact spot where the different clans are buried

The most prominent point upon the battlefield is the large memorial cairn set roughly midway between the opposing front lines. Around the memorial are many, although not all, of the grave markers. These are poignant, simple memorials and many visitors will search out a marker associated with their own clan.

The stones were erected along with the memorial cairn, in 1881. Geophysical tests confirm that there are many mass graves around the stones but how the names on the stones were chosen remains a mystery. In the confused aftermath of the battle, it is unlikely that those who had fallen would be separated into individual clan graves. It would have been difficult, if not almost impossible, to identify who belonged to which clan. The soldiers did not wear the brightly coloured tartans associated with clans today. Instead, the only outward symbol of clanship would be a badge or clan plant worn in a cap. It is thought that the stones are symbolic of those clans who fought for the Jacobite cause at Culloden.

As Professor Murray Pittock, one of the leading historians studying the Jacobite era has said, “Culloden as it happened is in fact much more interesting than Culloden as it is remembered.” If you are interested in a tour around Culloden Battlefield with a More2Scotland guide they will help you find out about both the fact and the fiction that surrounds this world-famous battle.

.

Recent Comments